ARTIST PROFILE

Jeanne Staples

Capturing the Moods and Moments of Island Life

Profile by Karla Araujo

Edgartown painter Jeanne Staples is a study in contrasts. Though classically trained and a realist in her own work, she cites abstract artist Mark Rothko as a major influence. And, while a clear, unwavering sense of self-discipline propels her into the studio nearly every day for eight hours at a stretch, she embraces ambiguity in life and strives to impart an air of mystery in much of her work.

In spite of her contradictions – or perhaps because of them – Jeanne has become one of the Vineyard’s most successful and highly respected painters, as well as a dedicated humanitarian who has devoted countless hours to help the people of Haiti through PeaceQuilts, an arts-based nonprofit organization she founded in 2006.

Represented by The Granary Gallery in West Tisbury and its affiliate, North Water Gallery in Edgartown, Jeanne is a member of Boston’s Copley Society of Art and a frequent participant in juried shows there as well. Her oils grace the walls of Edgartown’s l’Etoile Restaurant, and are part of the permanent collections of the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital and Farm Neck Golf Club, both in Oak Bluffs, and on view at The Vineyard Golf Club.

“There’s so much to inspire me on the Island,” Jeanne says. “This community offers wonderful riches. I appreciate the opportunity to show my work here and to work with a public that appreciates realism.”

A native of Lynn, MA, Jeanne first traveled to the Vineyard for brief vacations as a teenager. She returned with her own family over twenty years ago, soon scheming, she says, about how to move to the Island full-time. She and her husband purchased a piece of land in Edgartown, built a home they could also use as a rental property, then moved to the Island year-round from up-state New York eighteen years ago.

Introduced by her parents to art through childhood visits to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Jeanne pursued art, communications and education at Ithaca College, Colgate University, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the oldest art museum and school in the U.S. She credits the latter’s emphasis on rigorous classical training with laying the groundwork for her accomplishments.

“The Academy trains artists to thoroughly know their craft,” Jeanne explains. “I really embraced my studies and have used what I learned there throughout my career.”

She attributes her admiration for modern art to her position as Coordinator of Education for the Empire State Plaza Art Collection in Albany featuring works by such abstract expressionists as Rothko and Jackson Pollock, as well as sculptor Claes Oldenburg.

“Developing programming designed to explain to the public how to access the work led me to a deeper understanding as well,” she says. “And it brought a different perspective to my own work. Rothko’s deep saturation of color was awe-inspiring. It fills your field of vision. It was a surprise and a significant inspiration.”

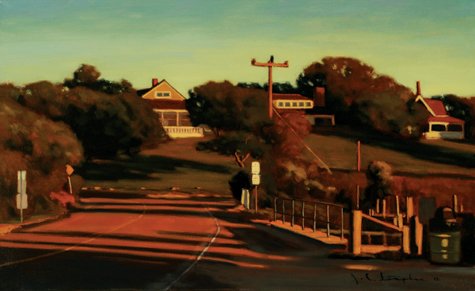

Less surprising is Jeanne’s affinity for the work of Edward Hopper, the quintessential American realist painter of the twentieth century. The parallels are easily drawn: Both render interpretations of the landscape, architecture and, occasionally, the people who inhabit them, relying on the play of light and shadow, with moods evoked by various times of the day. Both also share a geographical context. Jeanne’s maternal ancestors established a Nova Scotian village in the seventeenth century, giving her a deep-rooted attachment to the picturesque rural North Atlantic coastline, not dissimilar to that of the Vineyard. Hopper, following his own childhood on the Hudson River in New York, spent many summers in coastal Maine and Massachusetts, eventually building a home in Truro on outer Cape Cod where he lived for most of his last forty years of life. Both artists’ predilections for the region’s blocky, traditional shingled buildings and shoreline are evident in their landscapes.

There is also a sense of solitude – often melancholy – in both artists’ works, particularly those that include figures. Their landscapes are generally unpopulated; people, when they are depicted, tend to reflect an air of isolation and ambiguity, leaving viewers to extrapolate their own narrative meaning from the images.

Jeanne readily acknowledges her debt to Hopper’s influence: “People often see echoes of Edward Hopper in my paintings. When I was in art school I saw a retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art. I relate to his light, atmosphere, reduction of detail, and emphasis on form.”

Her present work divides neatly into three different bodies. The first, her landscapes, represent the majority of her focus. With simple, direct titles like “Approaching Storm, East Chop,” “Aquinnah Cliffs,” and “House at Edge of Field,” Jeanne’s confident depictions of the Vineyard capture, with varying treatments, the Island’s transcendent light, sweep of sky, steep roof pitches, smudged softness, deep purple-blues, and strong geometries of form.

“Present Pending,” Jeanne’s second body of work, will become a series of twelve to fourteen interrelated paintings. Both figurative and landscape, they convey a single moment in time, each from a different perspective. And, while the paintings can be appreciated independently, Jeanne intends them to “function collectively to create a single narrative.” To that end, the discerning viewer can detect recurring elements – a deck of cards, a painting on the wall of a living room, a window, a segment of a still life. Together, the series suggests a story, a connection among the characters in each adjacent setting, but, according to the artist, how it unfolds is left to the viewer’s imagination.

“I’ve created an ambiguous narrative,” Jeanne explains. “I want the viewer to pick up relationships between the paintings but I hope to convey a sense of mystery about them. It’s up to the viewer to fill in the blanks.“

Jeanne’s third series of paintings is an exploration in three dimensions. “I was intrigued by the idea of a 3-D painting,” she says. Inspired both by the stereoscope of the mid-nineteenth century that was used to view paired photographs, as well as by posters hyping the 3-D movies of the 1950s, Jeanne created different pairs of paintings to be viewed simultaneously through mirrors at a custom-crafted “viewing table.” Her goal: to engage the viewer in an interactive experience and to see if she could create 3-D works in her classic and painterly approach.

“It was a little tongue in cheek,” she confesses. “It was very fun for me – a different experience of making art.”

As for her subject matter, Jeanne says she selects images to which she forms an emotional connection, those which offer a “little bit of mystery.” Rather than seeking subjects that she finds “fully defined,” she instead chooses to create scenes in which both she and the viewer can explore “a bit of intrigue.” She explains: “Like everyone, I form attachment to places, times of day, iconic views, buildings. But I also look for an unfamiliar perspective or a view that’s different. I have to be open to that moment.”

Viewers, she says, seem to respond to her expression of atmosphere and a specific moment in time. “From what they tell me,” she offers, “they connect first to my use of color. Hopefully, they also relate to that same moment they’ve experienced in their own lives.”

Allowing viewers to draw on their own experience is key to Jeanne’s perception of point of view in her work. She strives to strike a delicate balance between, as she says, “how much to put in and how much not to.” With an emphasis on giving the viewer room to interpret, she says she “never wants to spell it out.”

“I don’t need to and won’t have all the answers,” Jeanne explains. “I’m comfortable in life with some ambiguity. It makes it easier. It opens things up and helps me to consider all perspectives.”

Working out of a studio located just a mile from her home, Jeanne typically starts a new painting with sketches, on-site oil studies and inspiration from reference photographs. While she often created en plein air in the past, she now says she prefers the controlled environment of the studio, working on more than one image at a time, “respecting the rules of oils,” as she adds layers and allows them to adhere.

And, when she is not in the studio, she spends, as she says somewhat wryly, “every other waking minute” on her efforts to help the impoverished Caribbean nation of Haiti. Nearly seven years ago, Jeanne initiated a pilot program to introduce skilled Haitian seamstresses to quilting, recognizing that the beautiful formal table linens they were designing no longer appealed to the average American consumer. Establishing a nonprofit organization, PeaceQuilts, Jeanne developed a network of independent women’s sewing cooperative businesses, owned by the women themselves. Today, PeaceQuilts is comprised of more than one hundred artisans in eight regions of the country, each crafting one-of-a-kind custom-designed quilts and quilted accessories for export to the U.S.

“They’re the owners and leaders now,” she explains. “We’re supporting coaches. We mentor them as artists and nurture their creativity. I’m inspired by them as artists and the spirit of Haiti informs my own work.”

Traveling when she can, perfecting her French language skills, learning Creole, and enjoying her husband and two grown sons, Jeanne’s overriding passion for painting is unmistakable in her luminous renderings of Vineyard life, both real and imagined. A self-professed optimist, Jeanne says she feels strongly that her best work is yet to come.

“There’s more and more percolating each year,” she concludes. “I’m still learning all the time and it fires me up to work every single day.”

To view more of Jeanne Staples work, visit www.jeannestaples.com.

In spite of her contradictions – or perhaps because of them – Jeanne has become one of the Vineyard’s most successful and highly respected painters, as well as a dedicated humanitarian who has devoted countless hours to help the people of Haiti through PeaceQuilts, an arts-based nonprofit organization she founded in 2006.

Represented by The Granary Gallery in West Tisbury and its affiliate, North Water Gallery in Edgartown, Jeanne is a member of Boston’s Copley Society of Art and a frequent participant in juried shows there as well. Her oils grace the walls of Edgartown’s l’Etoile Restaurant, and are part of the permanent collections of the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital and Farm Neck Golf Club, both in Oak Bluffs, and on view at The Vineyard Golf Club.

“There’s so much to inspire me on the Island,” Jeanne says. “This community offers wonderful riches. I appreciate the opportunity to show my work here and to work with a public that appreciates realism.”

A native of Lynn, MA, Jeanne first traveled to the Vineyard for brief vacations as a teenager. She returned with her own family over twenty years ago, soon scheming, she says, about how to move to the Island full-time. She and her husband purchased a piece of land in Edgartown, built a home they could also use as a rental property, then moved to the Island year-round from up-state New York eighteen years ago.

Introduced by her parents to art through childhood visits to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Jeanne pursued art, communications and education at Ithaca College, Colgate University, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the oldest art museum and school in the U.S. She credits the latter’s emphasis on rigorous classical training with laying the groundwork for her accomplishments.

“The Academy trains artists to thoroughly know their craft,” Jeanne explains. “I really embraced my studies and have used what I learned there throughout my career.”

She attributes her admiration for modern art to her position as Coordinator of Education for the Empire State Plaza Art Collection in Albany featuring works by such abstract expressionists as Rothko and Jackson Pollock, as well as sculptor Claes Oldenburg.

“Developing programming designed to explain to the public how to access the work led me to a deeper understanding as well,” she says. “And it brought a different perspective to my own work. Rothko’s deep saturation of color was awe-inspiring. It fills your field of vision. It was a surprise and a significant inspiration.”

Less surprising is Jeanne’s affinity for the work of Edward Hopper, the quintessential American realist painter of the twentieth century. The parallels are easily drawn: Both render interpretations of the landscape, architecture and, occasionally, the people who inhabit them, relying on the play of light and shadow, with moods evoked by various times of the day. Both also share a geographical context. Jeanne’s maternal ancestors established a Nova Scotian village in the seventeenth century, giving her a deep-rooted attachment to the picturesque rural North Atlantic coastline, not dissimilar to that of the Vineyard. Hopper, following his own childhood on the Hudson River in New York, spent many summers in coastal Maine and Massachusetts, eventually building a home in Truro on outer Cape Cod where he lived for most of his last forty years of life. Both artists’ predilections for the region’s blocky, traditional shingled buildings and shoreline are evident in their landscapes.

There is also a sense of solitude – often melancholy – in both artists’ works, particularly those that include figures. Their landscapes are generally unpopulated; people, when they are depicted, tend to reflect an air of isolation and ambiguity, leaving viewers to extrapolate their own narrative meaning from the images.

Jeanne readily acknowledges her debt to Hopper’s influence: “People often see echoes of Edward Hopper in my paintings. When I was in art school I saw a retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art. I relate to his light, atmosphere, reduction of detail, and emphasis on form.”

Her present work divides neatly into three different bodies. The first, her landscapes, represent the majority of her focus. With simple, direct titles like “Approaching Storm, East Chop,” “Aquinnah Cliffs,” and “House at Edge of Field,” Jeanne’s confident depictions of the Vineyard capture, with varying treatments, the Island’s transcendent light, sweep of sky, steep roof pitches, smudged softness, deep purple-blues, and strong geometries of form.

“Present Pending,” Jeanne’s second body of work, will become a series of twelve to fourteen interrelated paintings. Both figurative and landscape, they convey a single moment in time, each from a different perspective. And, while the paintings can be appreciated independently, Jeanne intends them to “function collectively to create a single narrative.” To that end, the discerning viewer can detect recurring elements – a deck of cards, a painting on the wall of a living room, a window, a segment of a still life. Together, the series suggests a story, a connection among the characters in each adjacent setting, but, according to the artist, how it unfolds is left to the viewer’s imagination.

“I’ve created an ambiguous narrative,” Jeanne explains. “I want the viewer to pick up relationships between the paintings but I hope to convey a sense of mystery about them. It’s up to the viewer to fill in the blanks.“

Jeanne’s third series of paintings is an exploration in three dimensions. “I was intrigued by the idea of a 3-D painting,” she says. Inspired both by the stereoscope of the mid-nineteenth century that was used to view paired photographs, as well as by posters hyping the 3-D movies of the 1950s, Jeanne created different pairs of paintings to be viewed simultaneously through mirrors at a custom-crafted “viewing table.” Her goal: to engage the viewer in an interactive experience and to see if she could create 3-D works in her classic and painterly approach.

“It was a little tongue in cheek,” she confesses. “It was very fun for me – a different experience of making art.”

As for her subject matter, Jeanne says she selects images to which she forms an emotional connection, those which offer a “little bit of mystery.” Rather than seeking subjects that she finds “fully defined,” she instead chooses to create scenes in which both she and the viewer can explore “a bit of intrigue.” She explains: “Like everyone, I form attachment to places, times of day, iconic views, buildings. But I also look for an unfamiliar perspective or a view that’s different. I have to be open to that moment.”

Viewers, she says, seem to respond to her expression of atmosphere and a specific moment in time. “From what they tell me,” she offers, “they connect first to my use of color. Hopefully, they also relate to that same moment they’ve experienced in their own lives.”

Allowing viewers to draw on their own experience is key to Jeanne’s perception of point of view in her work. She strives to strike a delicate balance between, as she says, “how much to put in and how much not to.” With an emphasis on giving the viewer room to interpret, she says she “never wants to spell it out.”

“I don’t need to and won’t have all the answers,” Jeanne explains. “I’m comfortable in life with some ambiguity. It makes it easier. It opens things up and helps me to consider all perspectives.”

Working out of a studio located just a mile from her home, Jeanne typically starts a new painting with sketches, on-site oil studies and inspiration from reference photographs. While she often created en plein air in the past, she now says she prefers the controlled environment of the studio, working on more than one image at a time, “respecting the rules of oils,” as she adds layers and allows them to adhere.

And, when she is not in the studio, she spends, as she says somewhat wryly, “every other waking minute” on her efforts to help the impoverished Caribbean nation of Haiti. Nearly seven years ago, Jeanne initiated a pilot program to introduce skilled Haitian seamstresses to quilting, recognizing that the beautiful formal table linens they were designing no longer appealed to the average American consumer. Establishing a nonprofit organization, PeaceQuilts, Jeanne developed a network of independent women’s sewing cooperative businesses, owned by the women themselves. Today, PeaceQuilts is comprised of more than one hundred artisans in eight regions of the country, each crafting one-of-a-kind custom-designed quilts and quilted accessories for export to the U.S.

“They’re the owners and leaders now,” she explains. “We’re supporting coaches. We mentor them as artists and nurture their creativity. I’m inspired by them as artists and the spirit of Haiti informs my own work.”

Traveling when she can, perfecting her French language skills, learning Creole, and enjoying her husband and two grown sons, Jeanne’s overriding passion for painting is unmistakable in her luminous renderings of Vineyard life, both real and imagined. A self-professed optimist, Jeanne says she feels strongly that her best work is yet to come.

“There’s more and more percolating each year,” she concludes. “I’m still learning all the time and it fires me up to work every single day.”

To view more of Jeanne Staples work, visit www.jeannestaples.com.