ARTIST PROFILE

Cindy Kane

Where Art Meets Community

Profile by Nis Kildegaard

Perhaps the first thing you should know about Cindy Kane is that she is a passionate reader. She’s often described as a “self-taught” artist, but a favorite quote from John Kieran – “I am a part of all I have read” – comes closer to catching the truth.

“I love to study,” she says, “but I never did well in institutional settings. Had there been a place like the Vineyard Charter School when I was growing up in Virginia, I might have thrived more, but I just didn’t perform well in school. I’ve always been a reader, so I’ve never felt inadequate or uneducated.”

During the growing-up years that many people spend in college, Ms. Kane lived and worked at Yosemite and Grand Canyon National Parks, where she explored caves and documented the Anasazi pictographs that are an important part of her personal artistic vocabulary to this day. And she devoured biographies, finding her mentors between the covers of their books.

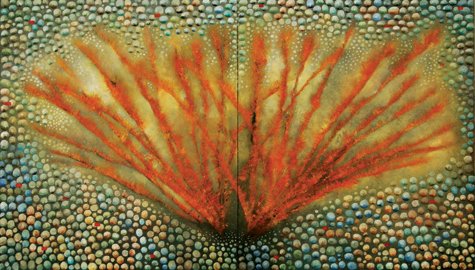

“I’ve always lived in offbeat places,” says Ms. Kane, “and I’ve always had an affinity for the outdoors.” Indeed, it’s impossible to look at her art without noticing how it reflects on our world from an offbeat place that is at once deeply engaged with the issues of our day, and yet subtly set apart. This artistic sensibility, this quirk of perspective, is of a piece with her chosen home for the past 15 years – the Island, in so many ways a microcosm of America, but with that bit of perspective that comes with living seven miles offshore.

In 1996, early in their marriage, Ms. Kane and her husband, master woodworker Doron Katzman, were living on a houseboat on the Hudson River with their first child, Tova, then a toddler. “We were looking,” she recalls, “for small towns to leave New York for.”

As much as she loves the city, she says, “It never really served me as an artist. I think a lot of people thrive on that intensity and sense of competitiveness, the multiplicity of things that are happening at any given moment. When I was living there, I think it overwhelmed me. New York kind of swallowed me up.”

A friend from a mothers’ circle on the Upper West Side suggested that Cindy and Doron take a look at Martha’s Vineyard. “I had no childhood experience here,” she says; “I thought it was just a place where people vacationed.” They drove up one day that February and connected with real estate broker Kate Grillo (who would later be teacher to both their daughters at the Tisbury School), and they spent two days looking at properties.

One place, an unfinished house in the woods of Sylvan Avenue in Vineyard Haven, appealed to them. “We made an offer the next day, not knowing a single person here. It just felt right. We moved here six months later.”

It was an intuitive leap, and absolutely the right decision. Looking back, Ms. Kane says, “It’s lucky that we came here in February, in the dead of winter. In August, the Vineyard probably wouldn’t have appealed to us in the same way.”

As newcomers to the Island, Ms. Kane and her family found it took some time to build connections. “This is the Northeast,” she says; “no one comes knocking at your door. And the arts community is very insular here. But I was determined to become a part of it, and there was no way to do that without being an activist.”

Her breakthrough came in 2003, when she invited more than 40 Island artists to respond to the war in Iraq on the medium of a single slate tile, 12 inches square. The result was ‘Artists Respond to War,’ a wall-to-wall installation at the Field Gallery, with all the proceeds from sales of the tiles going to Oxfam for war and famine relief.

“The act of putting paint on a canvas is an extremely intimate experience,” Ms. Kane says, yet much of her work reaches into that interface where art meets community and enters into the social dialogue. One enterprise that consumed her for two years was ‘The Helmet Project,’ which involved collecting memorabilia from 50 journalists who had worked on assignment in war theatres around the world. In the early stages of that project, she immersed herself in the writings of those war journalists. Then she covered 50 metal helmets with the authors’ handwritten notes and hung them in a circle, creating a haunting installation piece that was displayed on the Vineyard and in galleries across the country.

Ms. Kane admits to seeking out projects and subjects that bring opportunities for a kind of immersion. “I love to get stuck on something,” she says – “when you have your subject, it’s very liberating, and you’re excited to go to work. You’re not searching anymore; it’s just with you.”

A tour of Ms. Kane’s website provides a good introduction to the subjects and projects which have consumed her, sometimes for years at a stretch, in her artistic career. Online, her work is sorted by categories which include Feathers, Stones and Wings; Maps; Birds; Toys; Covers; Writers, and Rounds.

In the Toys category you’ll find artwork from the two years Ms. Kane spent on paintings inspired by the toys of her own children. “Maybe it was a way to say goodbye to that stage of their lives,” she says. “I was unaware of this then, but now in retrospect it seems so obvious.”

In the Writers category is a body of work that began one day in 2006 when Ms. Kane attended a talk by Island author Ward Just: “When I heard him talk about how he throws away so many pages a day when he’s working, I thought to myself, ‘I want those pages!’” She approached him; he contributed some of his typewritten scrap pages, and she began incorporating them into her art.

“Then I started asking more local writers,” Ms. Kane says, “and they were extremely generous.” As it turns out, although painting over the work of writers (and musical composers) is a practice that continues to fascinate her, she hasn’t found it easy. “At first,” she says, “I was intimidated by the words, and I found myself trying to preserve certain aspects of the look, or the handwriting, and my compositions lost something in that process. Consequently I reworked some of them. Now I know the secret that’s underneath, the pentimento of these notes that still peer through in little corners, but it’s not necessarily about the written word anymore.”

The category that has occupied Ms. Kane for the longest time, and that still is vital in her work today, is Maps. In such large works as her 2006 painting entitled ‘Migration’ – it measures almost seven feet square and resides in the permanent collection of The US Embassy in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina – she seems to be reaching for perspective on the place of humans on this planet. Those simple icons from her youth, the scurrying black stick figures, become individuals at close range and form patterns as the viewer steps back.

Ms. Kane returns to these tiny dancers in many of her paintings, sometimes juxtaposing their ancient forms with ominous images from our present-day collective unconscious – horizons on fire, mushroom-shaped clouds, landscapes smeared by the force of tsunami waves. Of the human figures, she says, “They go back to my caving experience with the pictographs, where you see these little vignettes, little stories, and you don’t really know what the story is – so the narrative is about anxiety, or transition.”

The artist insists she’s not trying to be deliberately secretive or obscure. Asked to decode a painting, she says almost apologetically, “I would if I could.” She adds, “Generally, if there’s something I want you to understand and reflect on in my paintings, hopefully it will become apparent.”

This summer, Ms. Kane worked with quilt artist Pam Flam to create an installation piece that filled an entire wall at the Chilmark Public Library. Her contributions are paintings that use covers of the New York Review of Books as a kind of informational substrate, layering images from human culture or the natural world over them. They have the poignancy of elegies, resonant with all the stresses that face the art and craft of the written word today.

Sharing some of the paintings she’s working on now for a fall show at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Ms. Kane admits that they don’t fall tidily into the categories of work on her website. This prompts a question about how she knows, as an artist, when it’s time to abandon one phase of work, one set of projects, and cast out in search of the next.

“You know when you begin to get bored. You realize that you’re repeating yourself – that’s very dangerous territory to go into.”

Cindy Kane maintains that after 16 years on the Vineyard she still has an urban mentality combined with a rural temperament, but that she can’t imagine a better place to call home. “The Island,” she says simply, “has all the qualities of small-town life we were looking for.

“I remember when we first moved here, feeling for the first year that if I should die, no one would miss me – I wouldn’t be mourned here. It takes a long time before you feel needed enough and appreciated enough in a community to be mourned. I do feel that we have that now, that we really do belong here.”

For more information about Cindy Kane’s work click on: www.cindykane.com

“I love to study,” she says, “but I never did well in institutional settings. Had there been a place like the Vineyard Charter School when I was growing up in Virginia, I might have thrived more, but I just didn’t perform well in school. I’ve always been a reader, so I’ve never felt inadequate or uneducated.”

During the growing-up years that many people spend in college, Ms. Kane lived and worked at Yosemite and Grand Canyon National Parks, where she explored caves and documented the Anasazi pictographs that are an important part of her personal artistic vocabulary to this day. And she devoured biographies, finding her mentors between the covers of their books.

“I’ve always lived in offbeat places,” says Ms. Kane, “and I’ve always had an affinity for the outdoors.” Indeed, it’s impossible to look at her art without noticing how it reflects on our world from an offbeat place that is at once deeply engaged with the issues of our day, and yet subtly set apart. This artistic sensibility, this quirk of perspective, is of a piece with her chosen home for the past 15 years – the Island, in so many ways a microcosm of America, but with that bit of perspective that comes with living seven miles offshore.

In 1996, early in their marriage, Ms. Kane and her husband, master woodworker Doron Katzman, were living on a houseboat on the Hudson River with their first child, Tova, then a toddler. “We were looking,” she recalls, “for small towns to leave New York for.”

As much as she loves the city, she says, “It never really served me as an artist. I think a lot of people thrive on that intensity and sense of competitiveness, the multiplicity of things that are happening at any given moment. When I was living there, I think it overwhelmed me. New York kind of swallowed me up.”

A friend from a mothers’ circle on the Upper West Side suggested that Cindy and Doron take a look at Martha’s Vineyard. “I had no childhood experience here,” she says; “I thought it was just a place where people vacationed.” They drove up one day that February and connected with real estate broker Kate Grillo (who would later be teacher to both their daughters at the Tisbury School), and they spent two days looking at properties.

One place, an unfinished house in the woods of Sylvan Avenue in Vineyard Haven, appealed to them. “We made an offer the next day, not knowing a single person here. It just felt right. We moved here six months later.”

It was an intuitive leap, and absolutely the right decision. Looking back, Ms. Kane says, “It’s lucky that we came here in February, in the dead of winter. In August, the Vineyard probably wouldn’t have appealed to us in the same way.”

As newcomers to the Island, Ms. Kane and her family found it took some time to build connections. “This is the Northeast,” she says; “no one comes knocking at your door. And the arts community is very insular here. But I was determined to become a part of it, and there was no way to do that without being an activist.”

Her breakthrough came in 2003, when she invited more than 40 Island artists to respond to the war in Iraq on the medium of a single slate tile, 12 inches square. The result was ‘Artists Respond to War,’ a wall-to-wall installation at the Field Gallery, with all the proceeds from sales of the tiles going to Oxfam for war and famine relief.

“The act of putting paint on a canvas is an extremely intimate experience,” Ms. Kane says, yet much of her work reaches into that interface where art meets community and enters into the social dialogue. One enterprise that consumed her for two years was ‘The Helmet Project,’ which involved collecting memorabilia from 50 journalists who had worked on assignment in war theatres around the world. In the early stages of that project, she immersed herself in the writings of those war journalists. Then she covered 50 metal helmets with the authors’ handwritten notes and hung them in a circle, creating a haunting installation piece that was displayed on the Vineyard and in galleries across the country.

Ms. Kane admits to seeking out projects and subjects that bring opportunities for a kind of immersion. “I love to get stuck on something,” she says – “when you have your subject, it’s very liberating, and you’re excited to go to work. You’re not searching anymore; it’s just with you.”

A tour of Ms. Kane’s website provides a good introduction to the subjects and projects which have consumed her, sometimes for years at a stretch, in her artistic career. Online, her work is sorted by categories which include Feathers, Stones and Wings; Maps; Birds; Toys; Covers; Writers, and Rounds.

In the Toys category you’ll find artwork from the two years Ms. Kane spent on paintings inspired by the toys of her own children. “Maybe it was a way to say goodbye to that stage of their lives,” she says. “I was unaware of this then, but now in retrospect it seems so obvious.”

In the Writers category is a body of work that began one day in 2006 when Ms. Kane attended a talk by Island author Ward Just: “When I heard him talk about how he throws away so many pages a day when he’s working, I thought to myself, ‘I want those pages!’” She approached him; he contributed some of his typewritten scrap pages, and she began incorporating them into her art.

“Then I started asking more local writers,” Ms. Kane says, “and they were extremely generous.” As it turns out, although painting over the work of writers (and musical composers) is a practice that continues to fascinate her, she hasn’t found it easy. “At first,” she says, “I was intimidated by the words, and I found myself trying to preserve certain aspects of the look, or the handwriting, and my compositions lost something in that process. Consequently I reworked some of them. Now I know the secret that’s underneath, the pentimento of these notes that still peer through in little corners, but it’s not necessarily about the written word anymore.”

The category that has occupied Ms. Kane for the longest time, and that still is vital in her work today, is Maps. In such large works as her 2006 painting entitled ‘Migration’ – it measures almost seven feet square and resides in the permanent collection of The US Embassy in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina – she seems to be reaching for perspective on the place of humans on this planet. Those simple icons from her youth, the scurrying black stick figures, become individuals at close range and form patterns as the viewer steps back.

Ms. Kane returns to these tiny dancers in many of her paintings, sometimes juxtaposing their ancient forms with ominous images from our present-day collective unconscious – horizons on fire, mushroom-shaped clouds, landscapes smeared by the force of tsunami waves. Of the human figures, she says, “They go back to my caving experience with the pictographs, where you see these little vignettes, little stories, and you don’t really know what the story is – so the narrative is about anxiety, or transition.”

The artist insists she’s not trying to be deliberately secretive or obscure. Asked to decode a painting, she says almost apologetically, “I would if I could.” She adds, “Generally, if there’s something I want you to understand and reflect on in my paintings, hopefully it will become apparent.”

This summer, Ms. Kane worked with quilt artist Pam Flam to create an installation piece that filled an entire wall at the Chilmark Public Library. Her contributions are paintings that use covers of the New York Review of Books as a kind of informational substrate, layering images from human culture or the natural world over them. They have the poignancy of elegies, resonant with all the stresses that face the art and craft of the written word today.

Sharing some of the paintings she’s working on now for a fall show at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Ms. Kane admits that they don’t fall tidily into the categories of work on her website. This prompts a question about how she knows, as an artist, when it’s time to abandon one phase of work, one set of projects, and cast out in search of the next.

“You know when you begin to get bored. You realize that you’re repeating yourself – that’s very dangerous territory to go into.”

Cindy Kane maintains that after 16 years on the Vineyard she still has an urban mentality combined with a rural temperament, but that she can’t imagine a better place to call home. “The Island,” she says simply, “has all the qualities of small-town life we were looking for.

“I remember when we first moved here, feeling for the first year that if I should die, no one would miss me – I wouldn’t be mourned here. It takes a long time before you feel needed enough and appreciated enough in a community to be mourned. I do feel that we have that now, that we really do belong here.”

For more information about Cindy Kane’s work click on: www.cindykane.com